WHILE much of the conversation around how the digital worlds have shaped our relationship to beauty can be reduced to superficial platitudes about social media being “bad” for us, Virtual Beauty, a new exhibition at London’s Somerset House provides a refreshing sense of optimism about how technology can help us subvert our understanding of beauty altogether.

Through showcasing works by more than twenty international artists, including pieces that pay homage to social media filters, the AI influencer Lil Miquela, and deepfakes, Virtual Beauty gets to the heart of how technology influences self-representation at a time when your online image-curation capacity is a form of currency offline too.

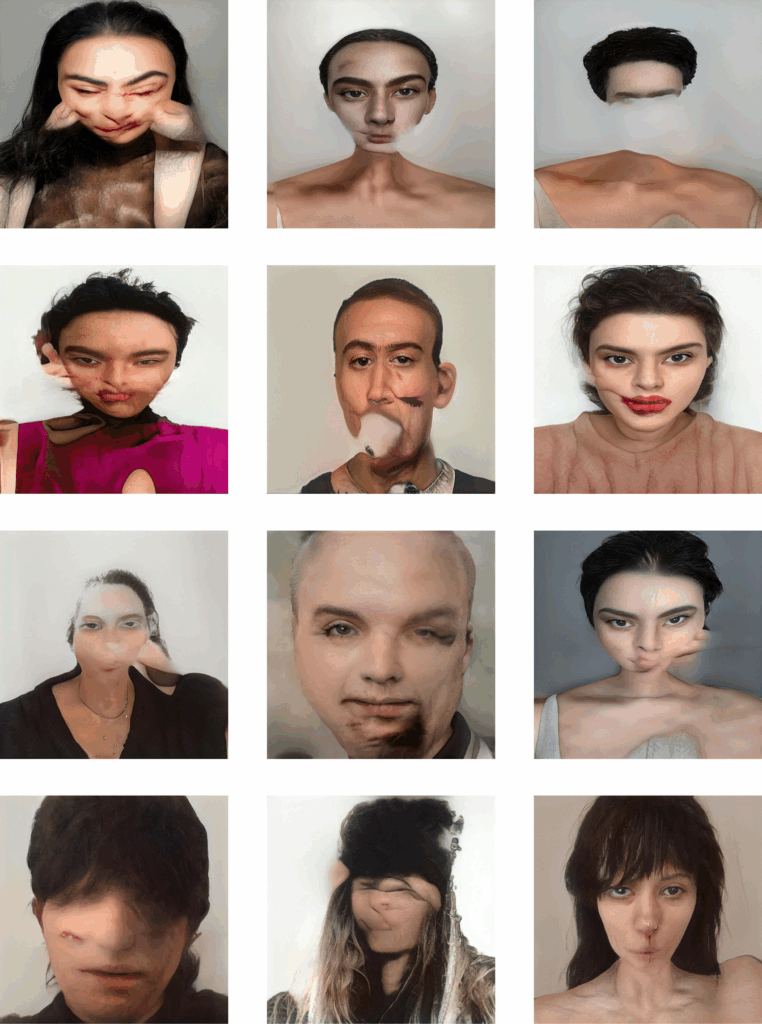

Ben Cullen Williams and Isamaya Ffrench. Past Life Grid (2021). Courtesy of the artist

It traces the trajectory of beauty in the digital era, with one exhibit showing 14 ‘iconic selfies; from over the years, including a screenshot of a Paris Hilton Instagram post in 2006 captioned ‘18 years ago today, @Britney Spears and I invented the selfie’, and another proclaiming that we have reached a ‘Post-Facial Era’ where recognition ‘no longer centres on the human face’

In what feels like a nod to the dystopian ease with which you can now pick a facial or body aesthetic and get a surgeon or a filter to enact it, a film installation called ‘You’ depicts a fictional commercial for a brain implant that allows you to pick any face you like, and post-operation, see it as yours whenever you look in a mirror.

Lil Miquela – Re-birth of Venus – courtesy of artist and @brud

More hopeful artworks invite us to expand our understanding of beauty beyond the confines of the traditional binaries of beautiful versus ugly, natural versus artificial, and masculine versus feminine.

Rather than promoting the reification of a new alternative or more inclusive standard, the power of Virtual Beauty lies in the curation of works that collectively challenge our ideas about beauty, creating a space to interrogate the politics underlying it.

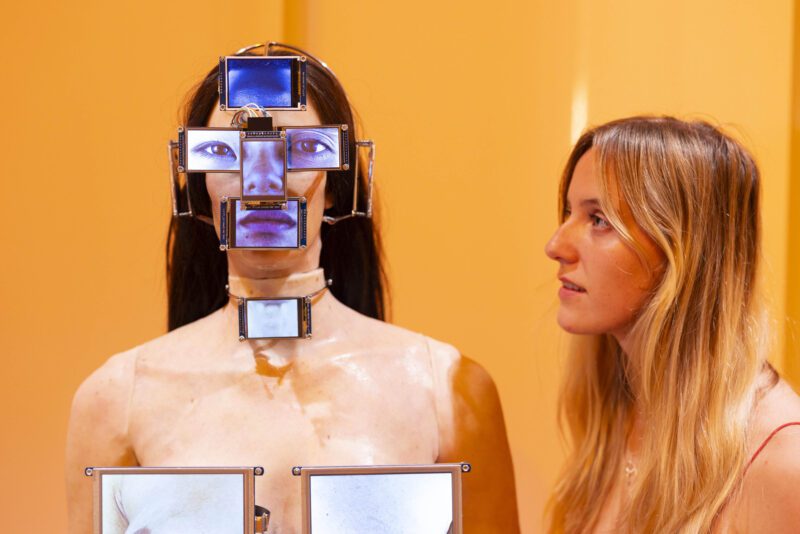

Filip Ćustić, pi(x)el, 2022 ©David Parry

Through this lens, as well as being undeniable facilitators of harm, emerging technologies and digital spaces are also presented as sites of hope, protest, and a gateway to reflecting on our ideas about what is ‘beautiful’.

There are artworks which depict luminous animal-like cyborgian avatars, forcing us to consider beauty outside of the spectrum we know it to exist on, as well as surrealist images of bodies that blur western gender norms, including a hyper-muscly individual in a black latex bikini with a Lara Croft style ponytail atop a bald head, set against a glittering purple backdrop.

The aim of works like these is ‘to create genderless identities beyond human canons of beauty’, with the enigmatic allure of the avatars depicted embodying gender fluidity and queer identity, evoking the way in which our presence in virtual worlds can influence perceptions of identity.

Ines Alpha: I’d rather be a cyborg (2024). Photograph: Li Roda-Gil. Courtesy of the artist

At its core, Virtual Beauty asks what beauty can become when the body is not the limit, with one artist, Ines Alpha, citing how technology enables her, as a woman, to feel like a subject rather than an object by giving her power and control over the version(s) of herself she presents.

For Alpha, an e-makeup artist who has previously worked with Prada, the surreal possibilities offered by fantastical digital make-up and virtual augmentation facilitate her liberation from traditional beauty standards.

By pushing at the boundaries of traditional beauty in this way, the exhibition creates a hopeful sense of optimism by disrupting the idea that it all ends at Instagram Face, a term coined by New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino to describe how ‘social media, FaceTune, and plastic surgery created a single, cyborgian look’ which is ‘ambiguously ethnic’, and marked by high cheekbones, poreless skin and catlike eyes.

At the same time, there is a sinister undertone to the exhibition. While one placard vaguely refers to the ‘manipulative nature’ of social media, others are more poignant, including one picture of two black women with braids in an image generated by AI, which reveals how racism is embedded into image generation tools. A lack of diversity in algorithmic training for generative AI means that these tools often distort back identity, here by giving the women pictured light skin and chemically straightened hair.

Another emphasises how gay dating culture has male beauty and body image being transformed by online gay dating culture, and one prompts a critique of ‘designer babies’ – referring to the modern fertility tech and hyper-consumerism which enables parents to decide a baby’s gender, eye colour, and complexion.

The final room of the exhibit contains videos showing an active project live on Instagram, which aims to reveal biases in Instagram’s content moderation rules, highlighting the platform’s algorithmic power to police body types.

The result is the presentation of the digital self as a site of tension, promising freedom while often mirroring the systems we hope to escape.

At its crux, Virtual Beauty asks us not whether beauty is liberating or constraining, but who holds the power to define and influence it in the era of Web 3.0? The answer might feel fixed, but hope comes from remembering that it is not.

by Meg Warren

Virtual Beauty at Somerset House is running from 23 July to 28 September 2025