Set in Ancient Egypt, Gianfranco de Bosio’s staging—a tribute to Aida’s historic 1913 edition—is blessed with perfectly troubled climaxes. Under conductor Daniel Oren the score soars and swoons.

VERDI’s Aida is, true to its roots, a tragedy: not quite operetta but more so a grand opera, with a plethora of the instantly excerptible set pieces of his famous creations. The plot is a hybrid too: a cousin to Nabucco but minus its wrathful final act, and with an impassioned throughline redolent of late Romanticism.

Veering between epics and tragedy, L’Arena di Verona’s staging culminates in one of the composer’s uneasiest endings, when the protagonists are denied not just a happy ending but also the more familiar Puccinian option of a woeful death.

Yet the drama still needs a context: Ramfis, the chief priest, tells Radames that the god Isis has picked the general who will lead the Egyptian armies into war against the Ethiopians. Radames prays to have been chosen in order to return victorious to Aida, an enemy slave in the Royal household for whom he cannot openly admit his love. Amneris, Princess of Egypt, secretly loves Radames and questions him about his feelings, suspecting that he prefers Aida to her.

L’Aida at L’Arena di Verona. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

It takes place within a society predicated on war and violence: a poignant mimicry of the troubled state of our world’s stage, barbaric and seething in equal measure. Tons were the traces of ancient Egyptiana that provided the decor of the opera’s traditional stagings. The literal references of Memphis and Thebes, Isis and Phtah were kept in the libretto—aside from a few columns scattered on the stage’s edges—but there were no pyramids, let alone elephants, to be seen.

De Bosio’s intention was to preserve the essential air of history and otherness that imbue Verdi’s tragedy while scrutinising its severity of purpose and darker underpinnings: the resonance of theocracy; the tension between desire and obsession; the price of betrayal when war brings forth its calamities to choose between love and family. He does so, though, in ways that don’t always cohere. His Egypt is a lavish ground that partially hides its wrath behind a veneer of civil glamour.

L’Aida at L’Arena di Verona. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

The monoliths and columns of Michele Olcese’s setting were arranged with precision and stuck firmly in place across a large fraction of the four acts, but costumes showed range and made for a compelling picture, allowing Oren’s score to draw continuous parallels between the ancient world and the modern times.

All this led to an occasionally puzzling first half, and it was not until the first interval that the opera began to settle. The second and third acts have imposing vibrancy and intensity, though de Bosio awakens the production’s pulsating vein by having an ensemble of dancers and choristers in full view rather than offstage.

There were some melodic unevennesses as well, though the evening was punctuated by a remarkable set of performances. Amneris (Princess of Egypt) interpreted by Ekaterina Semenchuk brought forth a fascinating character, invigorating in its amplitude at full throttle, yet also capable of sustaining beautiful, riveting pianissimos. She’s a fantastic actor, too, registering every shift of the princess’ torment.

Riccardo Fassi made a strong King, welding sound with sense to create a characterisation of great depth and tonal richness. Vocally, Fassi holds no terrors for his role: the reckless coloratura of the first acts is admirably secure and capped with a warm lower range; the lyricism with which he leads are at once weighty and superb; and the emotional and physical anguish of his scenes were even more powerful for being etched with such throbbing restraint. “The King essentially lacks a clear psychological depth, but in his scenes offers some quite recognisable declamation and chances to highlight the singer’s voice,” Fassi told GLASS in a preview.

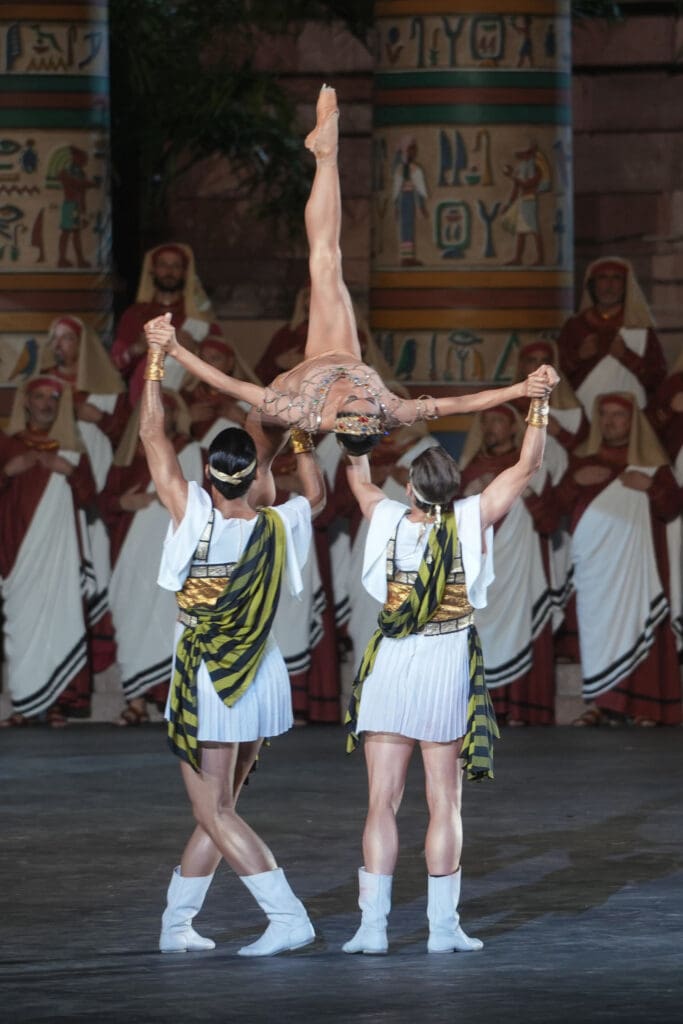

Principal Dancers Futaba Ishizaki, Gioacchino Starace and Denys Cherevychko. L’Aida at L’Arena di Verona. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

“Sadly Verdi didn’t compose an aria or at least a duet for this role, but the experience in Arena di Verona is definitely worth it;” he continues, explaining how, “Some roles like Timur in Puccini’s Turandot or Basilio in Rossini’s il Barbiere di Siviglia that I sang this season in Verona, offer more intriguing challenges vocally: however, performing on that stage is one of the most marvellous experience you can have theatrically, as you have to trust your technique and the projection of your voice.”

Speaking of projection and diaphragmatic support, Aida’s voice—performed by Russian soprano Elena Stikhina—is empathic, even though Act I didn’t show her best form, vocally speaking. Hers is a big, warm voice capable of soaring comfortably over a wide orchestra, but the lustre in her tone was slightly evident here.

On the foreground: Principal Dancer Futaba Ishizaki. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

In the following acts, she sounded brighter: O Patria Mia thrilled as it should. Little surprise though: She’s a superb actor, and the striking way she can fuse sound with elegance remained more or less intact in an ascending climax of scales. The dramatic, expansive lines suited her fractionally better, perhaps, than the sharpness of the high Cs and Ds, which give away a sense of ease but hold immense complexity in projection. “Performing the role of Aida at the Arena di Verona is an extraordinary and truly unforgettable experience,” enthuses Stikhina.

“The honour of stepping into such a historic role on a stage that has witnessed a century of iconic performances is something that stays with me every moment,” explaining how, to a large degree, “The Arena di Verona itself is a breathtaking venue, steeped in history, where the magic of opera comes alive in a way that few places can replicate; the energy of the audience, the grandeur of the setting, and the rich legacy of Aida at this venue all contribute to an experience that I cherish deeply.” Suggesting fragile beauty on stage through unsparing vividness, she believed in the intensity of her feelings for Radames and their power to wrath and overwhelm her.

L’Aida at L’Arena di Verona. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

But being overwhelmed by the opera’s virtuosity is, well, worth it. The vibrant energy of Susanna Egri’s choreographies (with coordination by Gaetano Bouy Petrosino) mirrors the conductor’s richly-crafted score, with its throbs, pulses and melodic rigour, the latter very much geared to the dramatically convincing Radames—performed by American tenor Gregory Kunde. His bronzed tone turns edgy while belting at the top, with a spine-tingling vibrato that gradually ratchets up the tension amid such the arena’s setting.

“The number one challenge is the heat”,” Kunde offered, explaining how “Performing outside is never easy. Costumes can be heavy and the stage can sometimes be challenging to move on, but all of that is always outweighed by the public’s response. I love singing here.” Big voices onstage can rip all manner of restraints to a riveting edge of thrill, and his performance made for such an example—blending passion and tension, emotively yet powerfully.

If Verdi’s pacing went occasionally askew on stage, dancers looked brilliant in the pit—projecting all the colour that made this impassioned and soulful Aida. Did it work? Yes, and if you took the principal dancers there are millions of reasons to watch the production with sharp insight. “As a Prima Ballerina, I had the incredible opportunity to dance the role of ‘The Slave’ in Aida (1913),” Futaba Ishizaki told GLASS.

Her innate sense of drama and wit painted a playful interpretation, with precise attitudes and fouettes. “Invited by Gaetano Petrosino (coordinator of the ballet) under Stefano Trespidi (Vice Artistic director of the Arena di Verona), and coached by Susanna Egri, who originally created this powerful role, I was guided through the complex emotions of the character, blending fear with the joy of freedom. This solo is iconic, packed with intense emotion and dynamic movement.”

Indeed, movement remains a glorious sight in the staging, and Denys Cherevychko dances it with loving care. “Dancing the lead warrior in the Triumph scene of Aida at the Arena di Verona for the first time was an experience beyond words,” Cherevychko opined in a preview.

“Performing Aida in its historic 1913 version, under the guidance of choreographer Susanna Egri, brought a deep sense of responsibility. Her meticulous attention to every gesture and movement is a reminder that dance is, above all, about conveying emotion and story.” One moment during the Pas de Trois stood out to Cherevychko, when the dancer representing Aida ran fiercely towards the warriors.

Principal Dancers Futaba Ishizaki, Gioacchino Starace and Denys Cherevychko. L’Aida at L’Arena di Verona. ©EnneviFoto / Fondazione Arena di Verona.

“Egri’s direction that she should be suspended in the air, momentarily overpowering the warriors, captured a moment of power and transcendence. Understanding the meaning behind this transformed my approach to the lift. Staying true to the choreographer’s vision is crucial, because for many in the audience, this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It’s moments like these that make performing so fulfilling, ensuring that every person in that arena felt the emotion and grandeur of the moment.”

And if the choreography doesn’t quite match the quavery challenge of the music, it’s fascinating enough, unfolding through groupings of dancers and lifts; the dancers, in fact, support each other suggesting a cohesive batch that’s dynamic and made for cheerful entertainment. “The role of the main warrior that I play does not have strong technical difficulties, but there are very complicated lifts with the woman,” concludes Gioacchino Starace.

“We are two male Principal dancers and one female Principal dancer, and to make the performance turn out in the best way requires concentration, mutual trust; feeling is the basis of this choreography. The wrong movement of just one of the three, could ruin the work of the others. We were lucky enough to work with and have in the room the choreographer Susanna Egri, a wonderful woman, capable of conveying all her knowledge and experience.” An experience that Starace, like his peers, ultimately used to perform with a sweet, sparkly and enjoyable verve—breaking away from Verdi’s mournful ending.

Thought-provoking, all of it.

by Chidozie Obasi