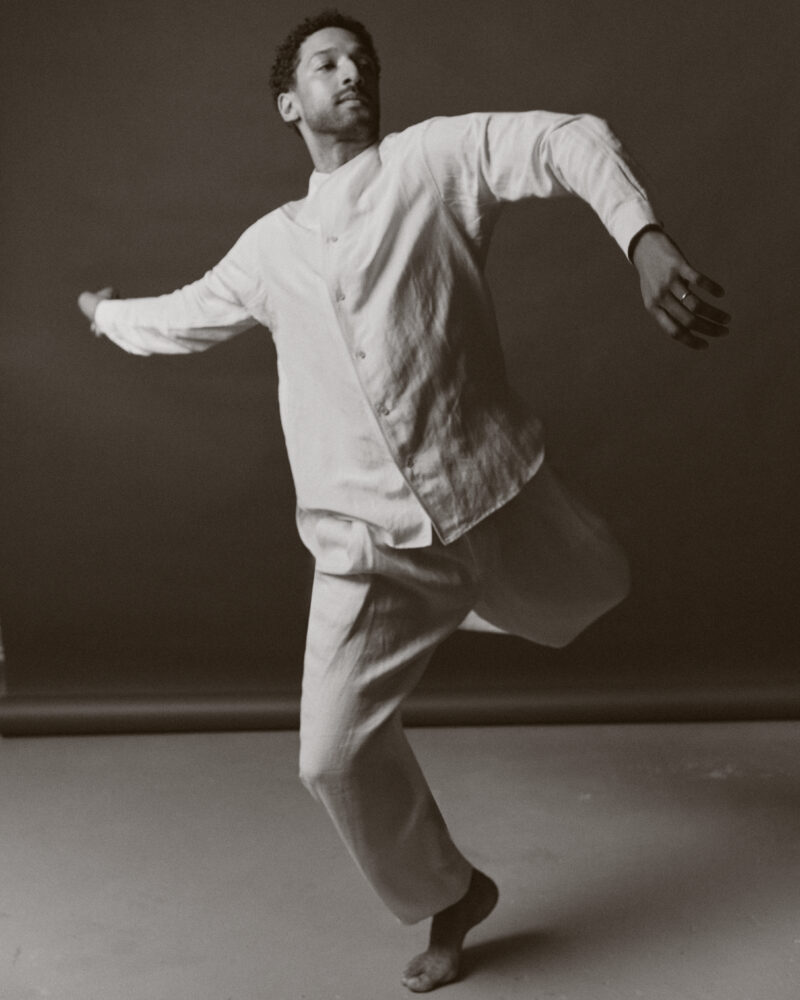

The Leverkusen-born, Tuscany-hailed choreographer and Artistic Director unpacks his joys, feels and thrills with GLASS—one emotion at a time.

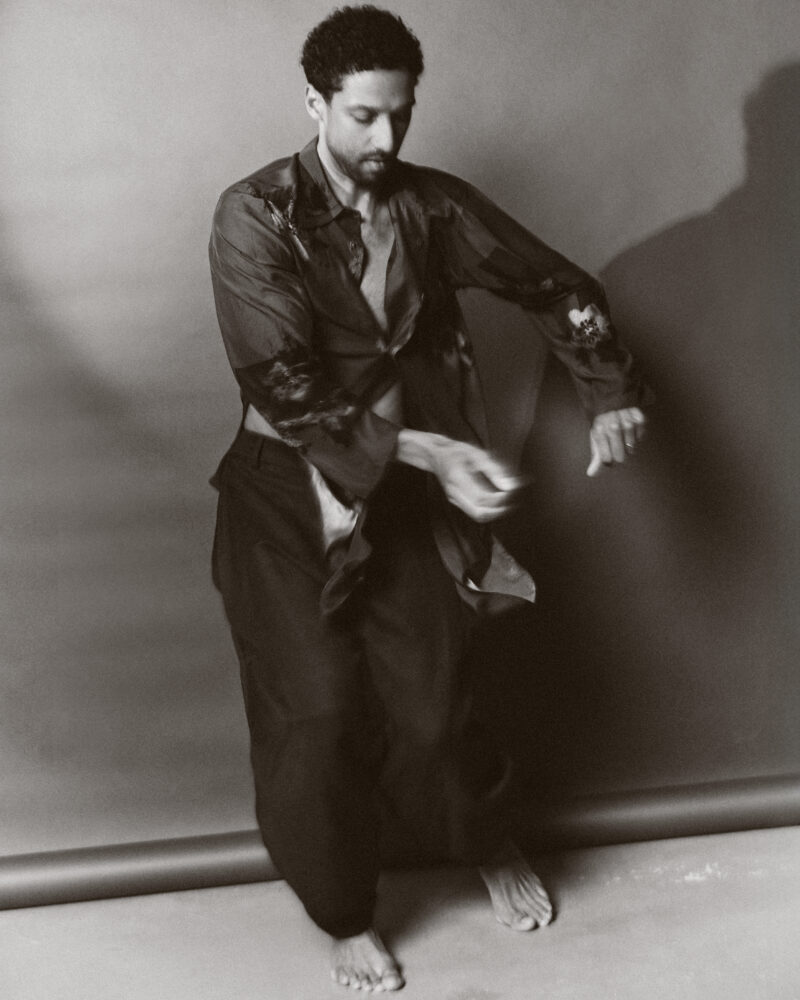

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

AT A TIME when shreds of social unrest are moving at an increasingly troubled pace, creativity continues to thrive in our world—refreshingly so for a field that is rooted in escapism and optimism. Once in a while, promising talents enter the creative cosmos: but what makes them so special?

All manner of adjectives could tempt us to unpack the above. Still, it’s surely more of an indescribable sensation, a poised effervescence, and a deeply unknowable yet searing energy that wraps our heads around them. That is very much the case for multi-hyphenate Philippe Kratz.

“My first memories of dance were with my mum, who brought me up as an only child in Germany,” Kratz recalls at the other end of the line, showing no signs of peacocking braggadocio on display. “She would have this thing where every once in a while—alongside her colleagues—they would go for dinner all together; they’d have these dinner nights, and one of them would mean going to Dusseldorf to have Lebanese food.”

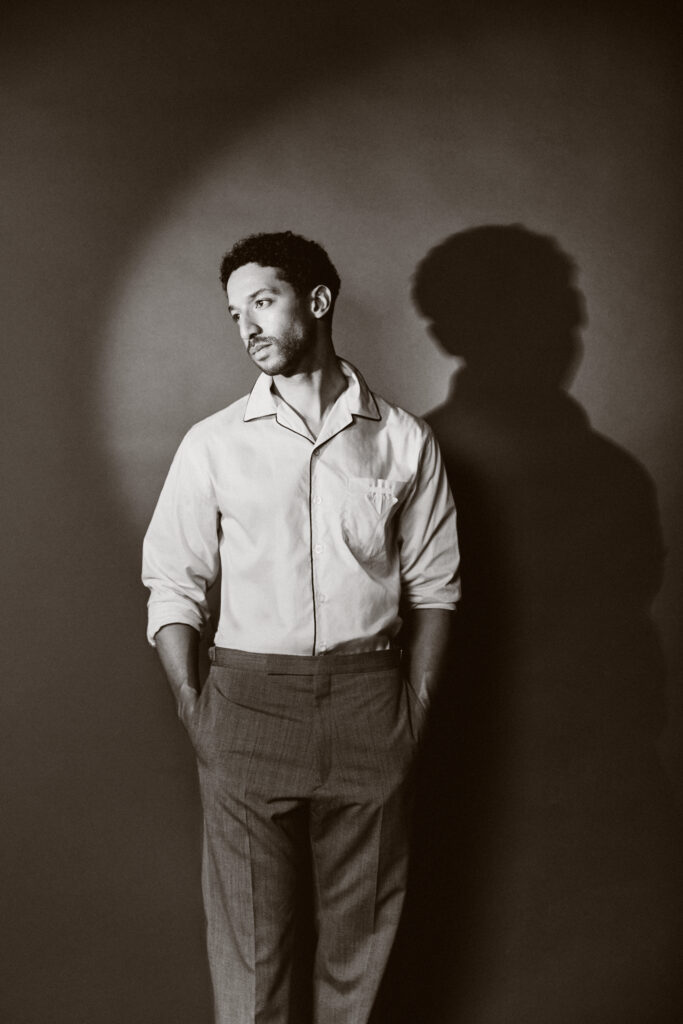

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

On one of those evenings, a Lebanese belly dancer came out and Kratz stood transfixed for a while gawking at her. “From that moment, my mum sort of felt there was something I needed to get out of my system, as many kids do,” he says. “She enrolled me in a dance school where I started taking ballet lessons, and I stuck with them ever since.”

Kratz was a dancer in Reggio Emilia’s Aterballetto for 13 years, and he’s been freelancing since 2021. “I began slowly detaching from the company during the pandemic and then took the big leap in 2021 when, for the second time, Manuel Legris invited me to Teatro alla Scala,” he opines. “I grew up in the Tanztheater tradition, which epitomises a fusion of dance and theatre, as you might know, by Pina Bausch.”

He went on to train in classical ballet at the Ecole Supérieure de Danse du Québec in Montréal and then at the Staatliche Ballettschule Berlin, graduating with A-levels. “My mum believed I needed to complete normal high school first,” he asserts. After that, he gained a degree as a professional dancer. “Back then, it was the first time I went into academic training, because before it was all a hobby.”

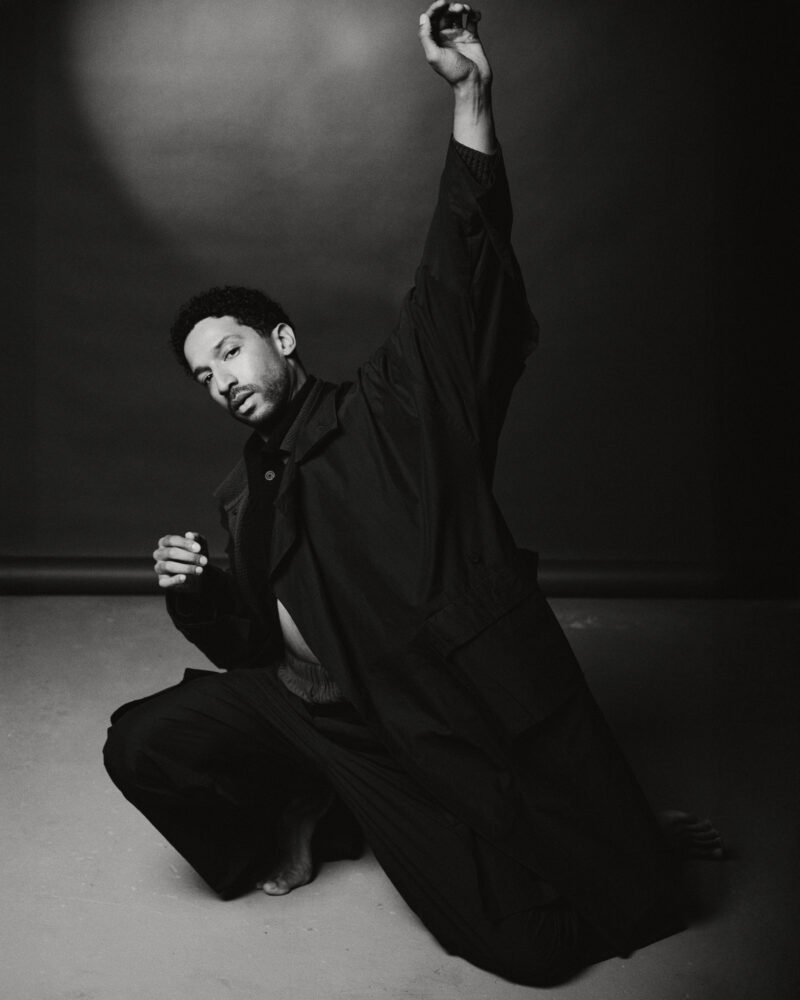

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

Kratz began his artistic path quite late, which proved to be a challenge at the start. “I was 17 years old and really had a lot of things to get in three years; It was kind of a wild ride,” he says. “I was at Staatliche Ballettschule Berlin, a school known for really rough classical Russian technique training, and for me getting all the information that everyone had absorbed in 12 years was quite a challenge.”

Earlier this year, Kratz collaborated on a creation with Tanzmainz, a Staatstheater in Germany, one of the most prolific and prominent contemporary dance ensembles in the country. “It’s a really beautiful company with a beautifully spirited collective of dancers,” he says. “They’re very versatile, as they come from different backgrounds, so it’s not even your typical upbringing in the dance world. But they have so many different tools and also nurture each other through them, which I found quite beautiful.”

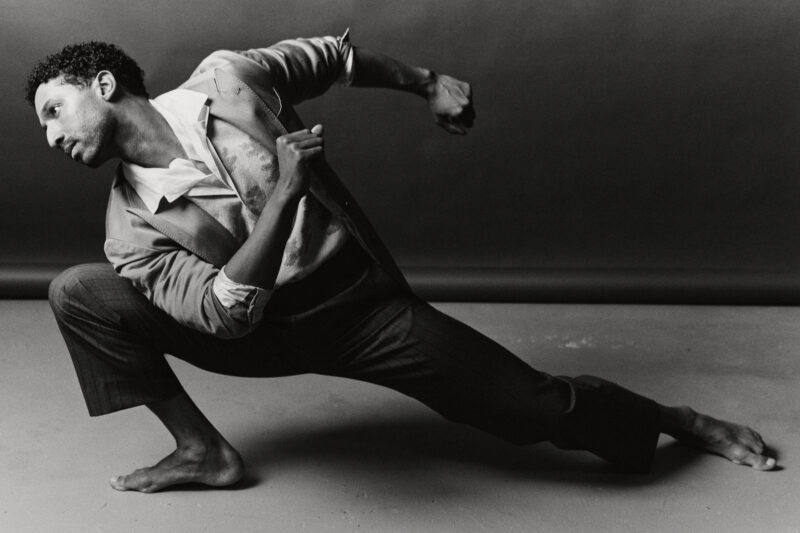

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

In March, he took on a job with a company working at the border between Luxembourg and Germany. “I did a piece on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which I unpacked the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice: something I really tried to squeeze the essence of. I loved the moments of longing, looking for someone, waiting in another world and then losing part of it in the end. I worked a lot on that.”

The end of February marked his reprise at Milan’s La Scala, along with the launch of a choreography that he staged for the National Ballet of Croatia and Zagreb in 2023, which has recently debuted at Rome’s Opera and Ballet.

What’s more, Kratz took over the Nuovo Balletto di Toscana, a contemporary dance company based in Florence. “It was Cristina Bozzolini that approached me: she’s one of the most prominent figures in Italian contemporary dance since the 1970s, when she first founded a contemporary dance collective outside of the National Theatre,” he argues.

On inspiration, he speaks frankly of how creativity and poetry went hand in hand in shaping his practice as a dancer. “I would say that the poet Fontane is one of my biggest inspirations, but James Baldwin and Pina Bausch are on the top list, too,” he opines, his face smiling. “I feel there’s a lot of poetry in what they do, which I find beautiful.”

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

After training in Montreal, he feels that the city had a lot of young people who were extremely creative and were pushing the scene forward. “I came across young choreographers coming into the school working with us, and I was incredibly fascinated by their brilliance and how they have a clear idea for bringing newness, intention and technical know-how,” he says.

“I was very intrigued by this way of not only being taught how to dance but also directing dance and showcasing an idea or an atmosphere. I had always done this also when I was in kindergarten. It was something that I was really interested in.”

With study, comes refinement. “I have a fascination for trying to fascinate people,” he says. “I don’t know, there’s something in this exchange of being looked at while dancing, but also giving back to who’s watching that I like.” Kratz is not a person who sets fixed goals for his career, but he’s trying to be more intuitive about what he wishes to do and where he feels like he needs to be. “The goal is never long term, it’s always short term: adjusting because situations change and maybe it’s just to protect myself from having expectations that can never be met.”

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

Kratz credits La Scala’s former Ballet Director Manuel Legris with the people who pushed his growth in pursuit of refining his dance expression. “We were at this competition in Beijing years ago, and he saw a piece of mine that I wasn’t even supposed to be dancing, but I did in the end,” he says. “And then Manuel told me he loved what I did, and asked if I could teach this for the Nureyev Gala that he was organising in Vienna; it was a beautiful experience, which led to me working with three beautiful artists.”

As the Director of the Nuovo Balletto di Toscana, Kratz’s company has been recently commissioned by this year’s Venice Dance Biennale. “We were the winners of the national call for creation by Sir Wayne McGregor, which of course is a beautiful honour for us, but also a beautiful opportunity to represent ourselves. I think this is going to be the moment in which the company is finally showing itself again after a while, because the company was supposed to shut down last year, which fortunately didn’t. Now we have a new managing director, Mario Setti, from Florence.”

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

Kratz stepped in as Artistic Director in July 2024, and he’s currently restructuring the company and weaving in new artists. “At the Biennale Danza, we have a shared evening with a piece of mine and a piece by Pablo Girolami, an Italian-Spanish choreographer and dancer based in Friuli,” he opines.

“I think it’s going to be a beautiful occasion to witness what we’ve been cooking and also what the company is able to do.” The evening is called A Smiling Sisyphus, stemming from a piece of literature by Albert Camus, published in 1942: it’s a tale of endurance, dignity and self-affirmation.

As a black artist in Italy, Kratz opens up about the complexities that thread through the country’s social tapestry. “I think in my career it happened maybe two or three times where I’ve mused over whether I was given this role because I’m black or maybe because there was a process behind it,” he reflects. “The moment you step outside the dance world, there’s always a fine line almost, a veil where you’re asking yourself how everything came to be. But for the most part, my path was very healthy,” he adds, explaining how, “I had a very beautiful career in Aterballetto, and I didn’t feel that exclusion played a role.”

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

Where he sees a bigger problem in Italy in general is outside the theatre. “I feel like the world of theatres and festivals are a safe space for me as an artist and for me as a black person,” he says. “Where I see more of a difficulty in Italy is once I step out of that bubble, as then it definitely gets more challenging not to be put into a corner. I feel like when you’re a brown person or a black person in Italy, you always have to work more, you always have to put more effort into it. Italy has quite a traditional view on things, which also doesn’t feel like it reflects the society that we all live in as Europeans.”

Moving on to lighter territory, his oeuvre was part of a triptych staged at La Scala earlier in Spring: an impassioned, poignant and punchy piece of artistry—under the wistful score of Radiohead—which envisioned a journey through time, shapes and space.

Photograph: Andrea Cenetiempo

“What I’m most interested in general and what I’m creating is an evolution which can stem from either a deconstruction or destruction or a reconstruction,” he says. “I’m very much interested in some sort of evolution, but within evolution, the revolution. What I really like is to witness a thread that stays unshattered. I love this idea of something always staying the same with everything else, like the calm in the midst of a storm or something like this. That’s really what fascinates me a lot. Something being so tough and so resilient that kind of goes unharmed.”

Through it all, there’s a kinetic language, a movement he’s trying to carve out and evolve that is very much in line with his technical background on one side, and with his sensitivity on another.

As we passed our allotted interview time, not only was I able to grasp the sheer devotion Kratz has towards the industry he deeply cherishes—but a deeper, soulful demeanour that left me pleasantly bewildered.

“We need to allow ourselves to be sensitive and kind with one another,” concludes Kratz. “Sensitivity doesn’t mean avoiding conflict, as I think it’s quite crucial to have conflict in order to evolve and to see each other’s perspective as well. But at the end, I hope we’ll reach an understanding, a compromise and stay open as much as it hurts.” And, just like Kratz, I very much hope the same.

by Chidozie Obasi

Photographer: Andrea Cenetiempo @andreacenetiempo

Stylist: Chidozie Obasi @chido.obasi

Hair: Alexander Markart @alexander_franzjoseph via @blendmanagement

Makeup: Giacomo Marazzi @giacomomarazzi_

Producer: Jessica Lovato @jessicalovato_

Fashion Coordinator: Davide Belotti @coccobeloooo

Fashion assistants: Luca Miceli @luca.miiceli + Loris Vottero @loris_vottero + Cloe Rubinato @cloe_rubinato + Jordan Max Baglioni @jordanbaglioni + Alberto Michisanti @albe.michi + Claudia Macera @claudiicante

Clothing credits:

Look 1: LORO PIANA

Look 2: PRADA

Look 3: HOMME PLISSÉ ISSEY MIYAKE

Look 4: Blazer, shirt BRUNELLO CUCINELLI | Jumper ZEGNA | Trousers MOSCHINO

Look 5: Jacket DIOR MEN | Shirt FERRARI | Trousers HERMÈS

Look 6: Jumper HERMÈS | T-shirt, trousers LOUIS VUITTON

Look 7: Coat, trousers DRIES VAN NOTEN | Jumper FENDI | Shirt SANDRO PARIS

Look 8: DRIES VAN NOTEN

Look 9: Shirt YOHJI YAMAMOTO | Trousers GIORGIO ARMANI