As the world’s global sociopolitical sector stands on the brink, it needs to broaden its gaze. Body of Evidence is a needed respite, currently exhibited at Milan’s Pavilion of Contemporary Art (PAC). Below, the Iranian polymath unpacked all-things creative practice and storytelling with GLASS.

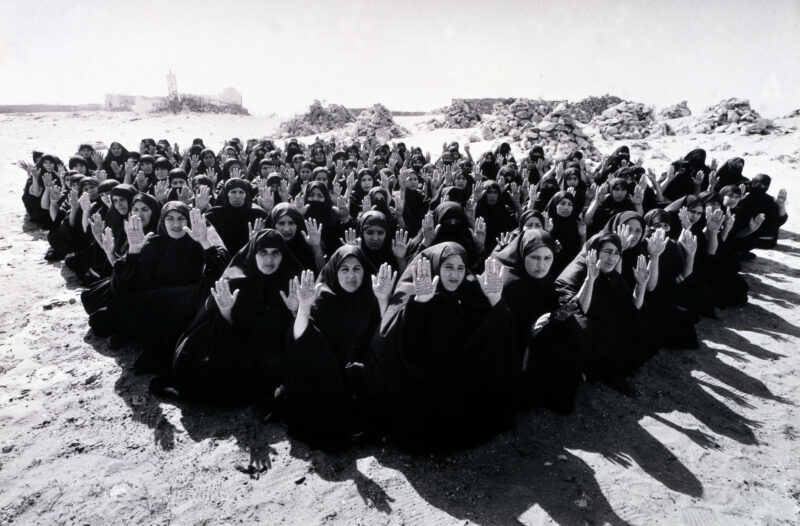

Rapture. Photograph: Shirin Neshat

MILAN, ITALY — The world’s societal crisis is failing us. It’s excluding stories, and talents, on and offscreen, and promoting only a “vile” number of narratives from sweeping backgrounds to ranks of wider relevance. These are not my modern thoughts. They’re the verdict of centuries of exploitation that see a one-sided gaze being constantly eulogised at the expense of those whose vile attempts at neglecting history sit at the core of their agenda.

However, the cruelties of our times are so brazen that they can no longer be brushed aside. An artist following this line of thought is Shirin Neshat: the Iranian-born, New-York hailed polymath creates work that dives into the notions of power, religion, race, gender and the relationship between past and present, through the lens of her personal experiences as an Iranian woman living in exile.

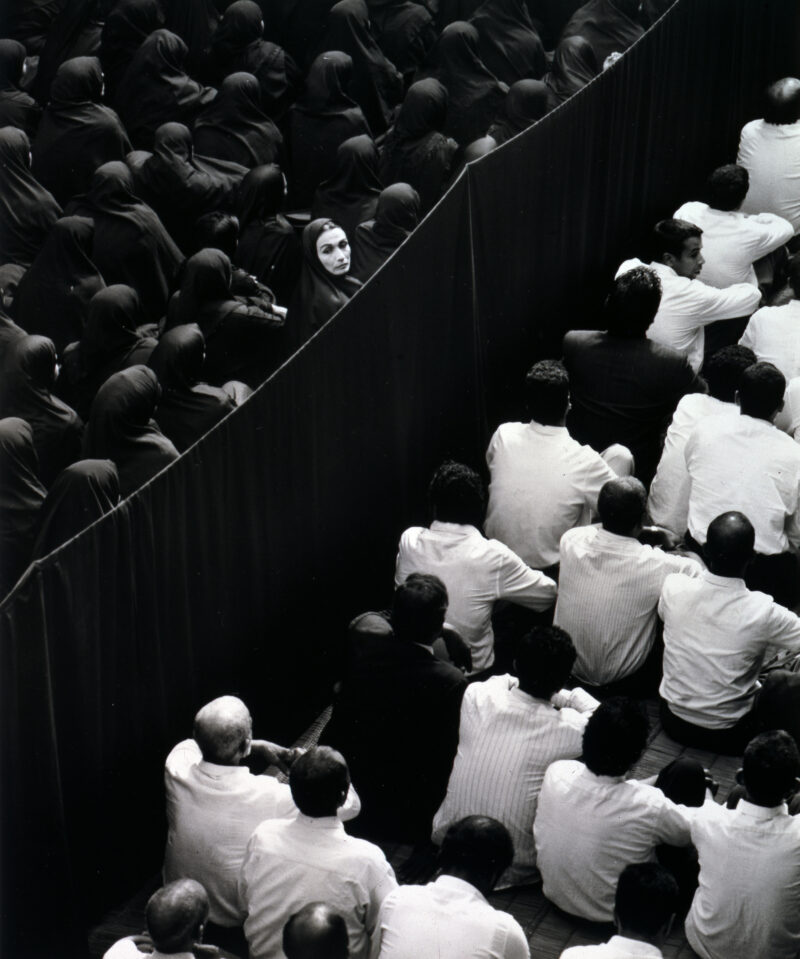

Neshat interprets her country’s culture from a female perspective: from her 1990s debut with the Women of Allah series, comprising photographs of women whose bodies are inscribed with poetic calligraphy, to The Fury, a video installation that anticipates a wealth of societal movements. Neshat’s work epitomises dualism and explores the tension between belonging and exile, sanity and insanity, dream and reality. Below, GLASS sat down with the artist.

Passage. Photograph: Shirin Neshat

How do you manage to dismantle the wealth of elements within your works, which stretch from religion, and culture to politics?

There’s aesthetics, there’s a visual vocabulary, a style and a methodology and then multiple ideas and meanings behind them: it’s really challenging because sometimes aesthetics takes over or sometimes the meaning is overly domineering. So for me, it’s always about finding the balance of carrying depth and meaning. I’m a minimalist, so I work on very simple body postures. For example, if you’re looking at these images from the Book of Kings, I thought of talking about the notion of patriotism and symbols of allegiance, which stand for the love of the nation universally. Then the writing over it reiterates that love.

And then could you justify your usage of monochrome over colour?

My work is so much about dualities, opposites, contradictions and paradoxes, so to me black and white punctuates that duality, but also I like this darkness of black and white. I think colour is pretty—as it tends to make things pleasant—but I don’t like that. There’s something about black and white that makes things more timeless. You know, when you’re using colour you have a deeper sense of time, but in black and white you forget about the period you’re in.

Film still from Colony, 2019. Photograph: Shirin Neshat

Film still from Colony, 2019. Photograph: Shirin Neshat

In these present times, the art world is facing severe downturns which makes it stand on the brink. Have you approached any new, exciting mediums?

Most things in art are about making money, but the reason I like videos and movies is because it goes away from making commodities and it really touches a variety of audiences. I like the idea of making videos and work that are not possible to buy. I think cinema is particularly a very powerful tool. I really love making films.

Fervor. Photograph: Shirin Neshat

How do you scrutinise the subjects that you pick for your photographs?

Well, it happens very organically. For example, this story about sexual exploitation was about a woman from Iran being sexually raped in prison and it was one of the stories I heard about: women that were abused by men in uniform. And it lived with me for a long time, so I thought that I must absolutely do something. Because for so long, I’ve made work about the female body as a point of shame or political ideology, but I’ve never depicted it as a sexual exploitation of violence.

So, I wanted to do that and that’s when I made this video. Moreover, Land of Dreams was my very first work about America, which got me thinking—as I’ve made work about my own dreams, now I go to Americans and ask about their dreams. So, it was playing with the idea of America being the land of dreams, and every project developed very organically according to what was going on in my life.

by Chidozie Obasi