I SAT for a portrait in my sweaty gym kit and ate fresh sourdough … and it was the perfect Sunday afternoon.

In a warehouse unit of dull corridors, peeling wallpaper and dusty air can be found the studio of British painter, Morag Caister. A den bathed in light – surprising, given that the large window looks out on a huge brick wall – with velour and corduroy armchairs and sofas acquired from the Facebook marketplace. Sketches and paintings are pinned to the walls and a threadbare geometric rug covers the entire space.

Morag Caister, a British artist based in London, has swiftly ascended in her career since graduating in 2019, with her work featured in prestigious collections including the National Portrait Gallery and Soho House.

In 2022, Caister’s exceptional talent was recognised when she won Sky Arts Portrait Artist of the Year TV series. This resulted in a commission to paint Sir Lenny Henry and, in further acknowledgment of her influence, Caister emerged as a candidate for Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe: Art & Culture in 2023.

Genti on Sunday, Oil on Paper, 90x90cm, 2022, Private Collection

At the core of Caister’s practice lies a profound exploration of existential concepts through figuration. Her artwork delves into timeless themes and cyclic patterns inherent in human nature, contributing to a rich tapestry of the human experience.

Drawing from live sittings, Caister captures the essence of her subjects through intricate, emotive lines that resonate with a sense of repetition. Her thoughtful use of colour, applied sparingly yet effectively, breathes life into her portraits, resulting in vivid and dynamic representations.

Curator and broadcaster Kathleen Soriano describes Caister’s work as “tender, truthful, touching”. Caister’s figures indeed possess a truthfulness that transcends mere replication, portraying characters that are genuine, candid and engaged.

Despite the fragmented use of colour that composes them, they possess fullness and wholeness within the space they occupy.

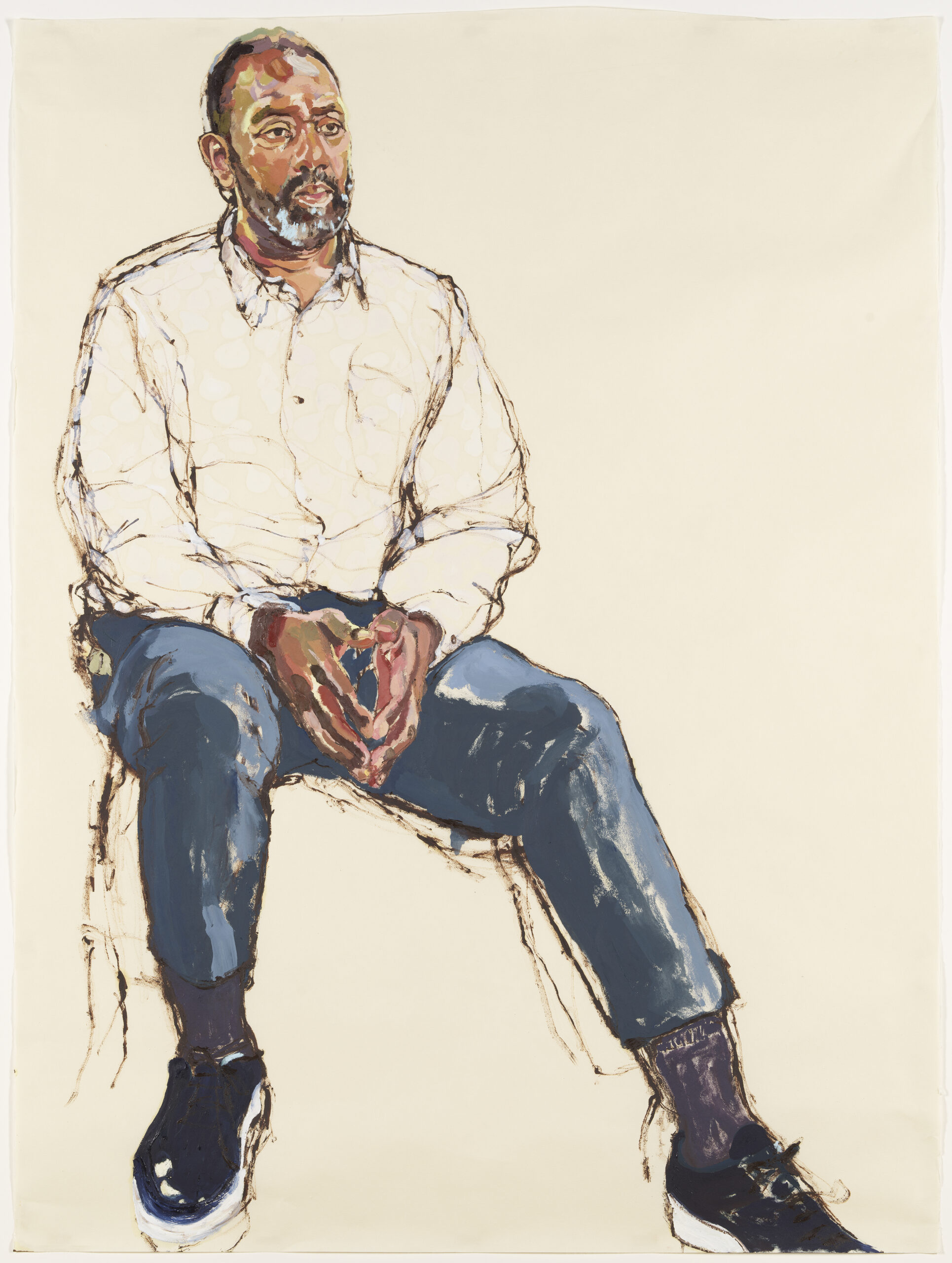

Sir Lenny Henry, Oil & Soft Pastel on Okawara Paper, 130x100cm, 2023, The National Portrait Gallery

Caister’s artistry reveals bodies that are delicately rendered, often appearing weightless and immersed in the surrounding emptiness. Her mastery of line, sensitivity of touch and deep understanding culminate in a captivating and distinctive artistic allure.

Portraiture, the practice of creating likenesses of individuals, has been a fundamental aspect of visual art since ancient times, providing a window into the lives, personalities and ideals of people throughout history. In early civilisations such as Egypt, Greece and Rome, portraits were often reserved for individuals of high status, such as rulers, gods and heroes.

They aimed to capture not only physical features but also convey the subject’s character and significance within society. The Romans, for instance, produced intricate sculptures and painted portraits known as “veristic” portraits, which emphasised the naturalistic depiction of ageing and individualised features.

Elizabeth Day, Oil on Paper, 100x70cm, 2022, Private Collection

During the Renaissance in Europe, portraiture experienced a remarkable resurgence. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Hans Holbein the Younger created lifelike portraits that emphasised both the physical appearance and the inner essence of their subjects.

The advent of oil painting techniques allowed for greater depth and detail, enabling artists to capture subtle nuances of expression and personality. Portraits during this era often depicted individuals from various walks of life, including royalty, merchants, scholars and artists themselves.

As society evolved, so did the concept of portraiture. The Enlightenment era saw a shift towards individualism and the exploration of human emotions and psychology. Portraits became a means of self-expression for both the artist and the subject, reflecting not only physical likeness but also the complexities of inner thoughts and emotions.

This trend continued through the Romantic period, when artists sought to emphasise their subjects’ emotional states and personal experiences.

Fast forward to the modern era, and portraiture has taken on new dimensions. The advent of photography in the 19th century revolutionised the way portraits were created. Photographs allowed for quicker and more accurate representations of individuals, leading to the democratisation of portraiture.

It became accessible to a wider range of people beyond just the privileged elite. The technological advancements of the 21st century has further expanded the possibilities for creating and sharing portraits, with digital media and social platforms enabling a global exchange of visual representations.

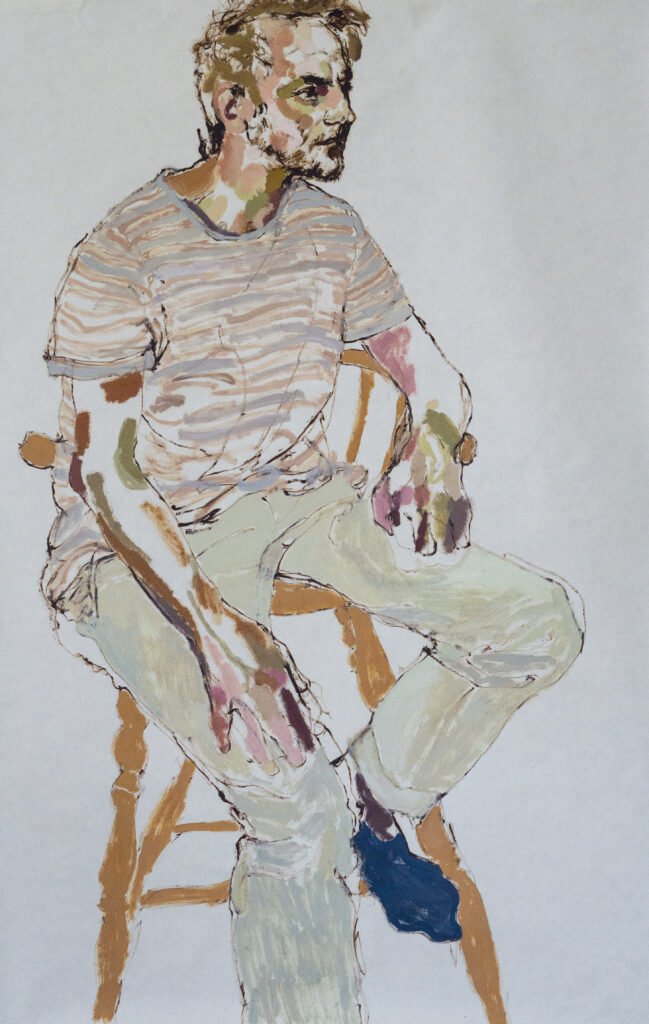

Genti in My Pink and White Jumper, 100x130cm, 2022

Ruth Millington’s work, particularly her book Muse, explores the intricate relationship between artists and their subjects in the context of portraiture. Through her writings, she delves into the dynamics of inspiration, collaboration and emotional connection that often exists between the artist and the person being portrayed.

Millington’s exploration sheds light on the multifaceted nature of portraiture, highlighting how it serves as a mirror reflecting both the subject’s identity and the artist’s perspective. This is certainly the case with Caister, whose hero is Alice Neel, whom she frequently contrasts with Lucien Freud.

The key difference between them, she tells me, is the artist’s acknowledgement of the importance of the sitter and the accompanying respect. Neel understands portraiture to be a kind of collaboration, as does Caister.

Caister makes sure I’m comfortable and isn’t fussed by my pose or posture as I wriggle into the armchair and pick grapes out of a punnet. We discuss life, our loves and our mutual acquaintances in the art world.

Genti (sofa series 5), Oil on Okawara Paper, 120x85cm, 2023

This isn’t the first portrait I have sat for and it’s comfortable in ways that others haven’t been, largely because I get to chat and listen and not sit in silence (something I’m not very good at). The scale of the painting was enormous and it was only as I got up to leave that I went behind Caister and looked at the painting.

I’d been watching her mix the white spirit into an earthy brown and apply quick, intentional strokes for a few hours and hadn’t even considered what I might look like; hair unwashed, oversized t-shirt, bruises on my thighs from walking into things.

Turns out, I was the picture of contentment. I was sunken into an armchair, legs stretched out and bent at the knee, my noodle arms laying across my stomach and hips. There was no expression yet on my face, but my head was tilted down and to the side, listening, comfortable. I felt seen, loved and accepted.

The history of sitting for portraits is a rich tapestry that weaves together art, culture and human connection.

As Millington reminds us, each portrait is a unique blend of creativity, perception and shared experience, and artists like Caister both celebrate the traditional values of portraiture and make space for these new conversations.

by Phoebe Minson